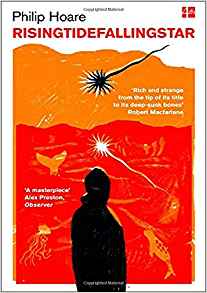

RISINGTIDEFALLINGSTAR

Philip Hoare

Like a conversation with an erudite friend. Not sure how thematically coherent it all was, but that didn’t matter at all.

Even during the day in the twenty-first century, a chill sea mist can envelop its springtime streets – all the seasons are delayed here – filling the glowing white lanes with ghosts. There are spirits throughout this creaking old town. You see their shadows on stairs, shapes out of the corner of your eye. In the winter, they walk down the street. They’re there in the summer too; they just look like everybody else.

Yet despite the intense cold – so barbarous it becomes a kind of warmth – the shore is full of life.

Marlow saw that ‘we live in the flicker, but darkness was here yesterday’.

My heavens, I think: sea or sky, it doesn’t seem to matter which. Everything is the same.

Whiteness was its aesthetic, an appalling pallor, a plastic dystopia fabricated from petrochemical products that were already starting to poison us.

Like Joseph Conrad, Stevenson saw darkness and domination reflected in the imperial sea.

There’s no accommodation of the human: no access, no mediation, no agreement. It’s all in dispute, with itself.

Charted in his letters, the slow, inevitable speed of Owen’s assumption into war is frightening and obvious, as if he were cycling into it. I look at his bookended dates and wish I could have written a different biography for him. Perhaps if he hadn’t written it all down, or if I hadn’t read it, it might not have happened. I might have seen him in the nineteen-seventies, an old man with a greying moustache on Meadfoot beach, looking out to sea, looking back into a past that never happened.

It was a war for natural resources, the first war of the Anthropocene, an augury of extinction. In 1917 Siegfried Sassoon was appalled to discover that the real aim of the conflict was ‘essentially acquisitive, what we were fighting for was the Mesopotamian Oil Wells’.

I had an overactive imagination, but what use is an underactive one?

A whale’s song alters each season, like fashion trends or musical styles. This cetacean transmission is evidence of a cultural exchange, ‘unparalleled’, as Ellen Garland and her fellow scientists note, ‘in any other non-human animals’. Whales are the only creatures other than us whose evolution has been shaped by culture, by learned behaviour passed on from mother to child.