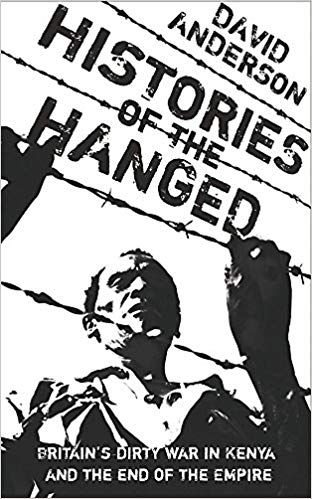

Histories Of The Hanged

Britain's Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire

David Anderson

Ugly stuff and very much a forgotten history. Perhaps less surprising that it’s not better understood in the UK, but even in Kenya it seems that only recently is it being properly re-examined.

The British have liked to imagine that their retreat from imperial grandeur was dignified and orderly. Above all in Africa, the British tend to think they made a better job of it than anyone else.

British justice in 1950s Kenya was a blunt, brutal and unsophisticated instrument of oppression.

They exploited Kenya to attain a quality of life that few could have aspired to elsewhere. The privileges of a landed aristocracy, by the early 1900s already under severe attack in Britain, could be had by almost anyone with a white skin in Kenya.

The slaughter of the Ruck family, at their farm in Kinangop on 24 January 1953, was to be the definitive moment of the war for the white highlanders.

This was my first experience of men and women who had momentarily lost all control of themselves and had become merged together as an insensate unthinking mass. I can see now individual pictures of the scene – a man with a beard and a strong foreign accent clutching his pistol as he shouted and raved; another with a quiet scholarly intellectual face, whom I knew to be a musician and a scientist, was crouched down by the terrace, twitching all over and swirling with a cascade of remarkable and blistering words, while an occasional fleck of foam came from his mouth.

Anyone reading these trial papers now could not help but be struck by the absurdity of the judge’s reasoning;

For Churchill, the ‘highly individualistic and difficult’ white highlanders were as much the problem as any rebel army.

London had decided that Kenya would have a multi-racial government, whether the white highlanders liked it or not.

Mau Mau, he said, was a ‘mind destroying disease’.

It was a neat argument: if Mau Mau was a mental illness, innate to the African in transition, then British colonialism could not be blamed

Kenya’s dirty war is not that it remained secret at the time but that it was so well known and so thoroughly documented. These things were not hidden. They were openly talked about in Kenya. They were reported to London on many, many occasions; and numerous individuals and pressure groups lobbied and campaigned, from as early as January 1953, to highlight the extent of the atrocities and abuses that were taking place.

Whereas elsewhere in Britain’s empire, most notably India, the prison graduates of the struggle to be rid of colonial rule were the political elite of the nationalist cause, in Kenya colonial incarceration was a far more widespread and pervasive experience. It has affected Kenya’s national psychology ever since.